While the sixteen-year-old Marcel Pinas (1971) was producing his drawings and watercolours at the Nola Hatterman Institute in Paramaribo, a bloody civil war was raging in his birthplace, the north-eastern district of Marowijne, between the forces of army leader Desi Bouterse and the guerrillas of his former bodyguard, Ronnie Brunswijk. Two realities existing side-by-side.

Five years later, in 1997, Marcel Pinas was a locally successful artist. His drawings and watercolours, often with indigenous themes, were popular. They came to him easily. The government gave him, together with Robert Enfield, George Struikelblok and Humphrey Tawjoeram, a scholarship to continue his studies at the Edna Manley College of Visual and Performing Arts on Jamaica. Here he was brought down to earth with a bang. It was now made very clear to him that if he was not prepared to deviate from his successful, but traditionally paved path, he may as well go straight back to Suriname. For the first time he was forced to reflect on what he wanted to say and express and to make his ‘modus operandi’ subservient to this. The one reality was being forced to look the other in the eye

The story behind his work

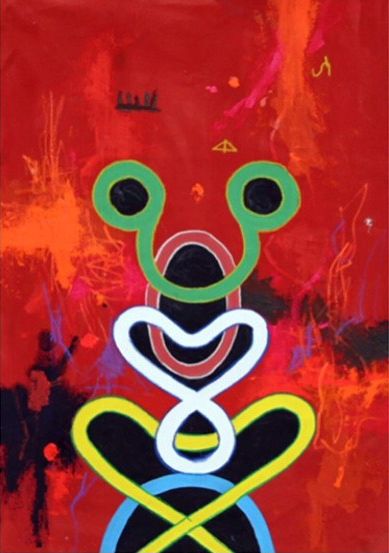

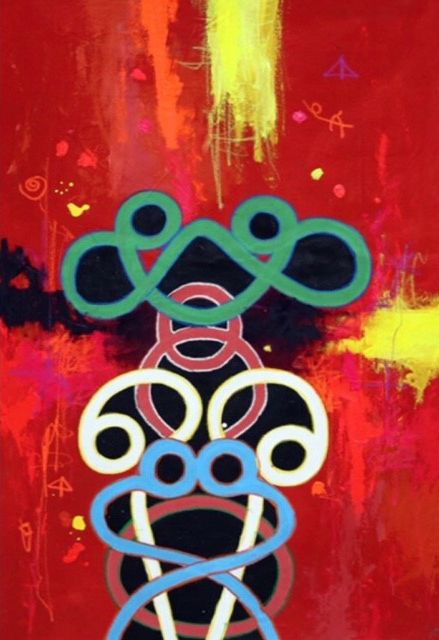

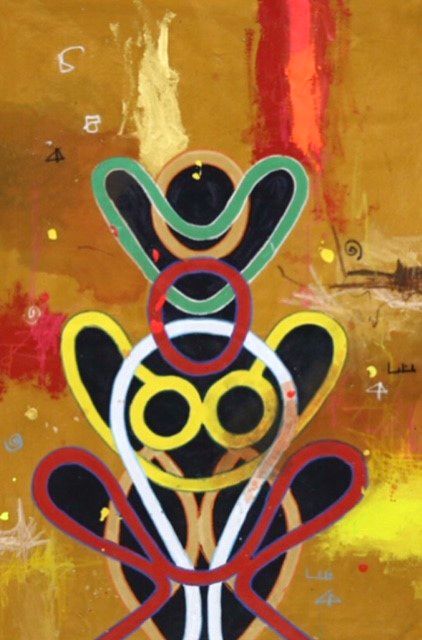

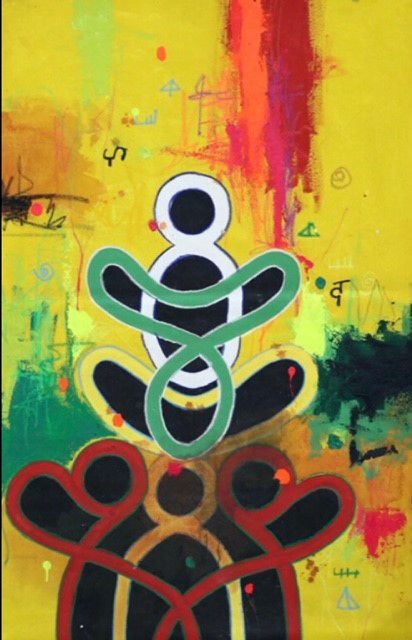

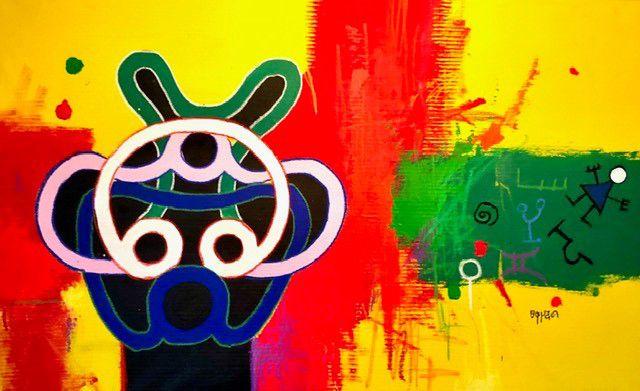

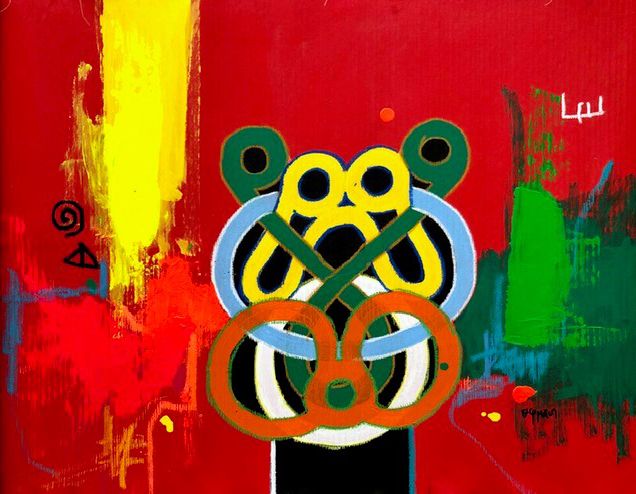

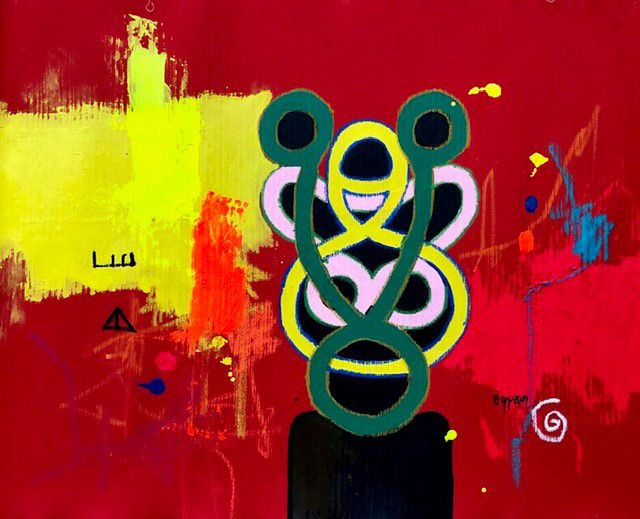

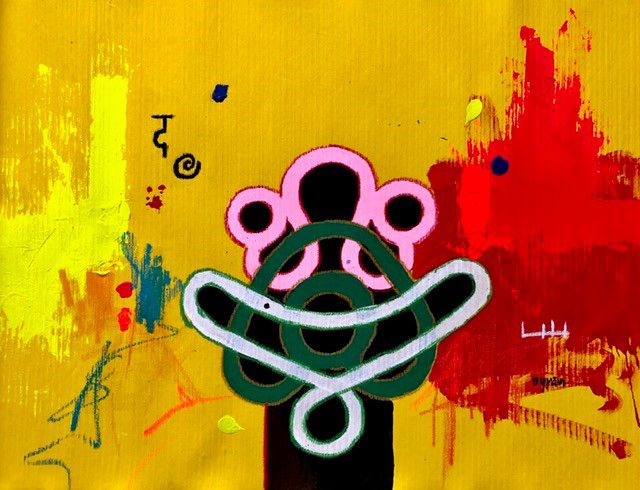

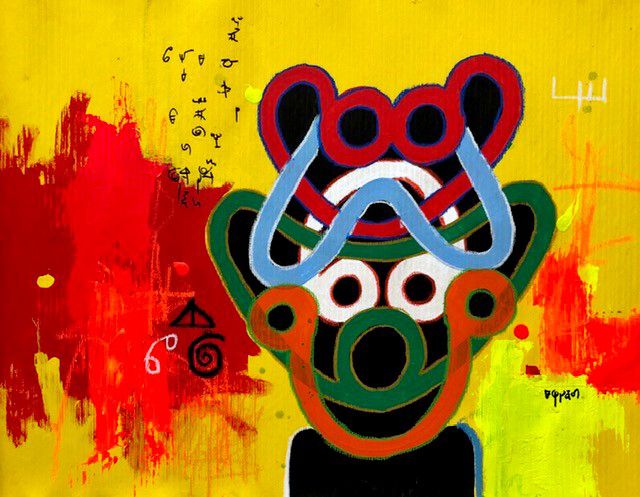

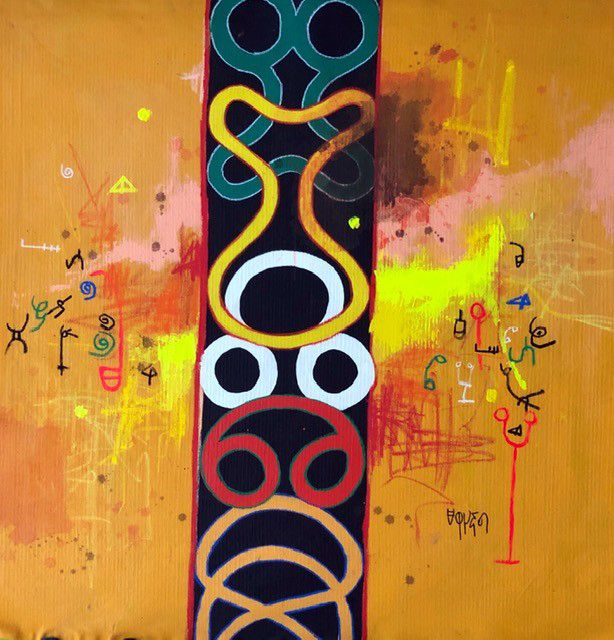

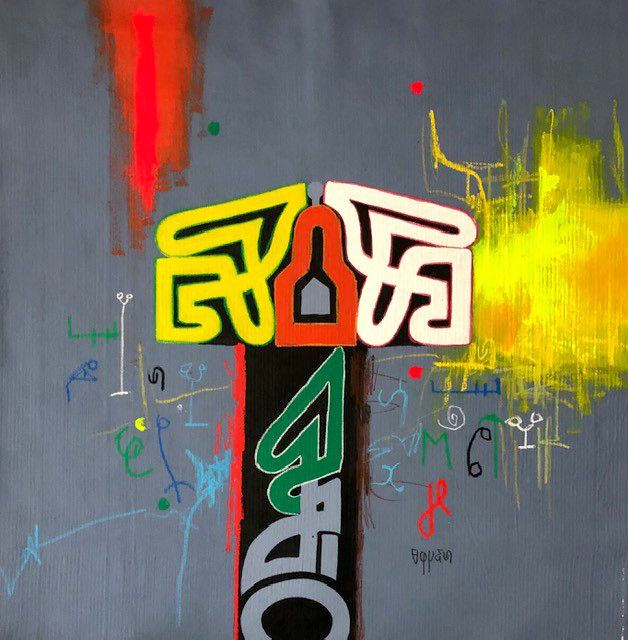

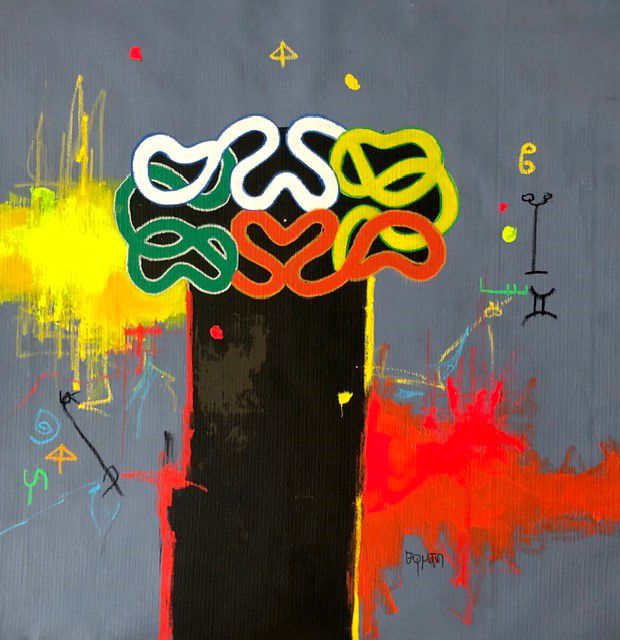

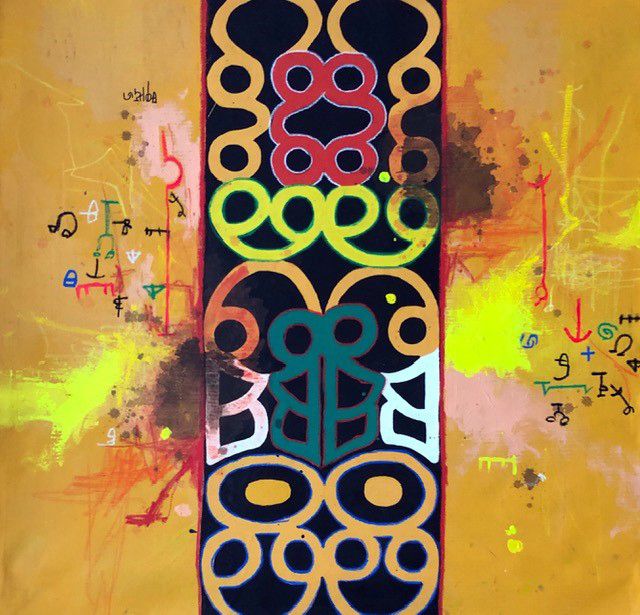

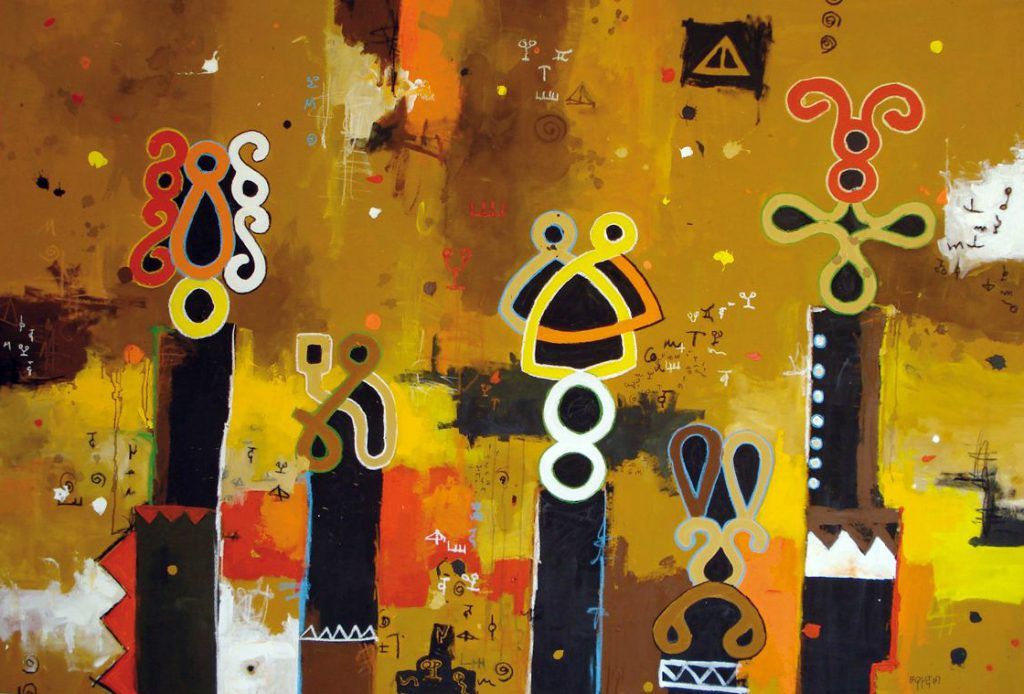

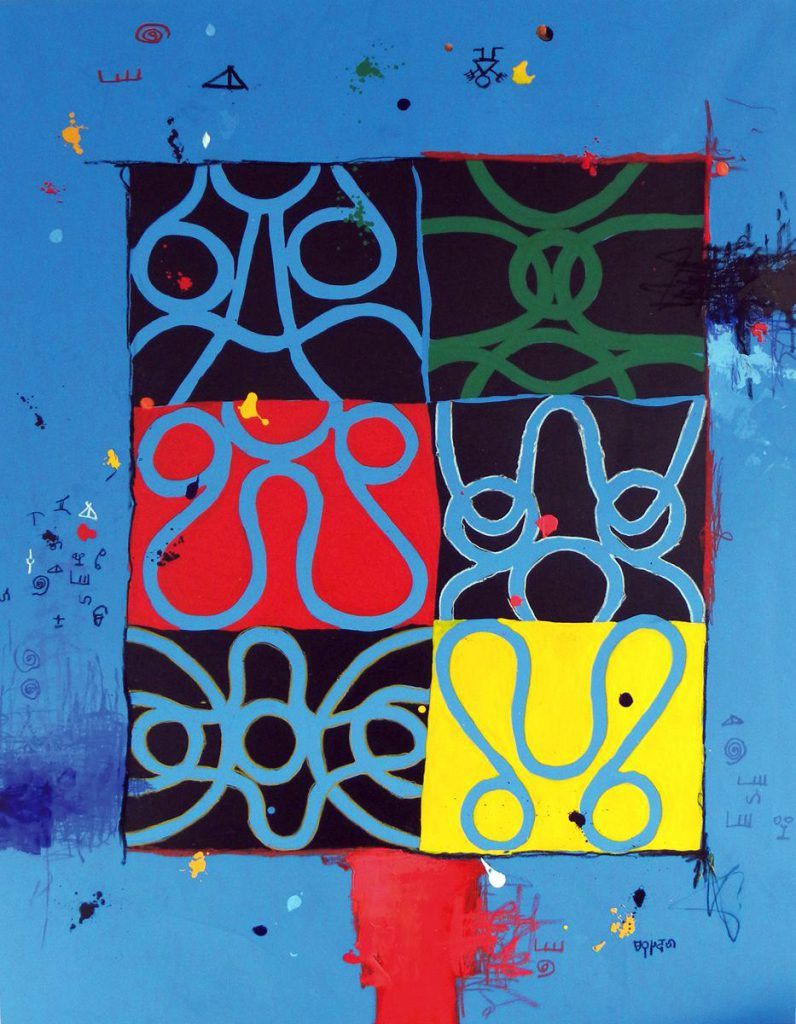

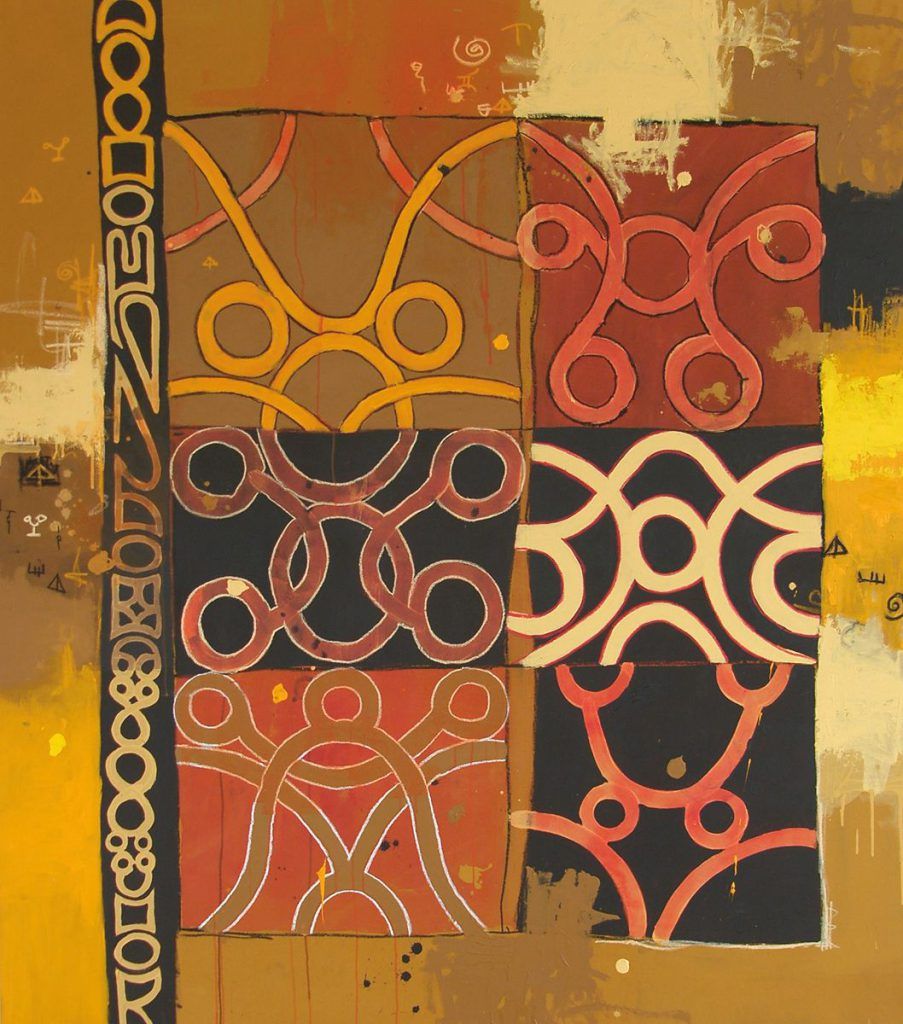

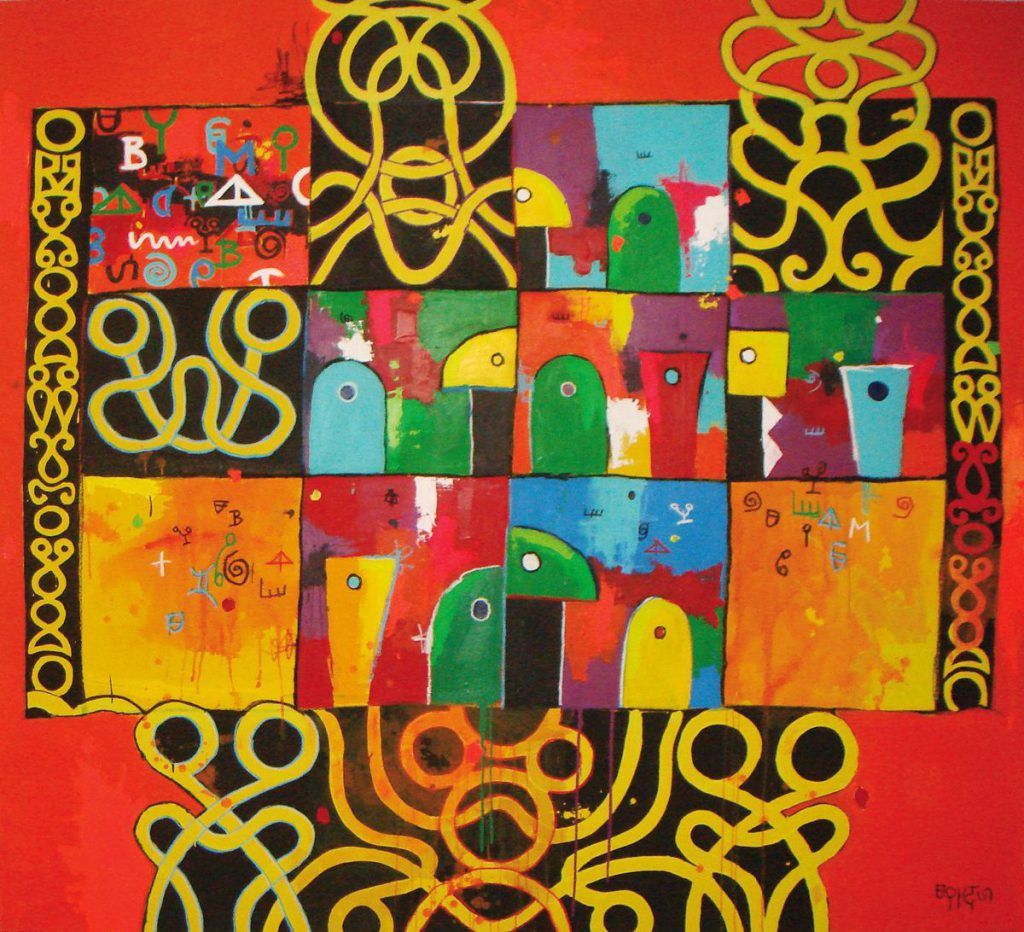

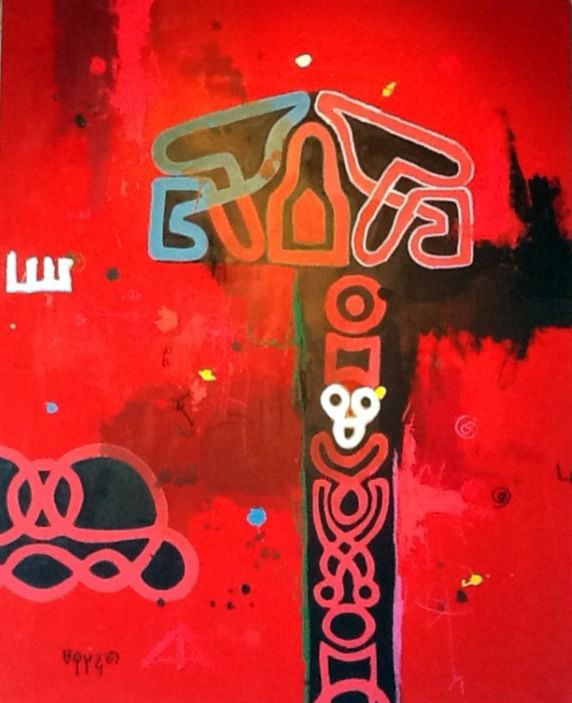

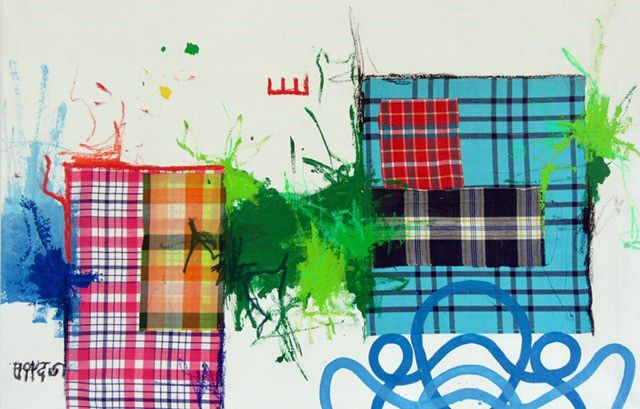

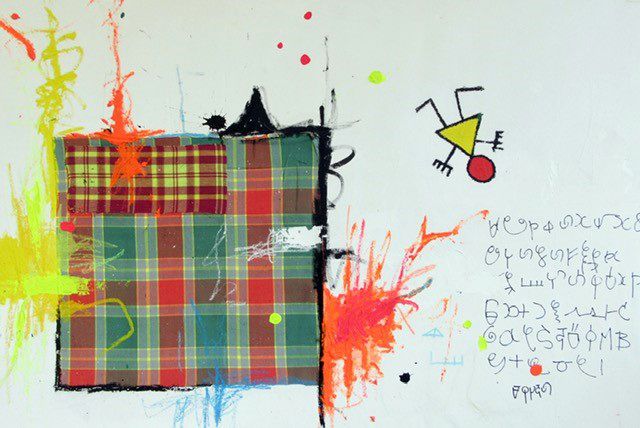

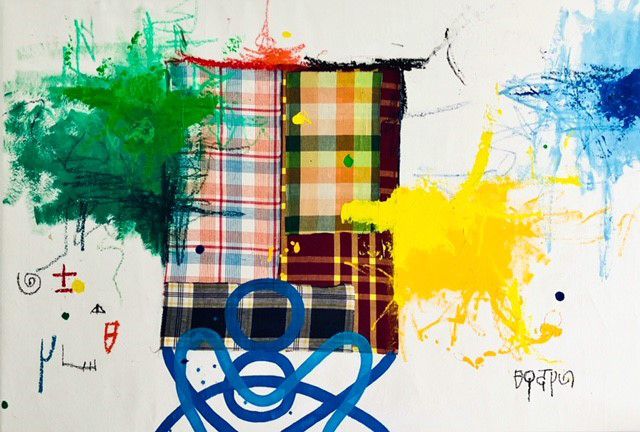

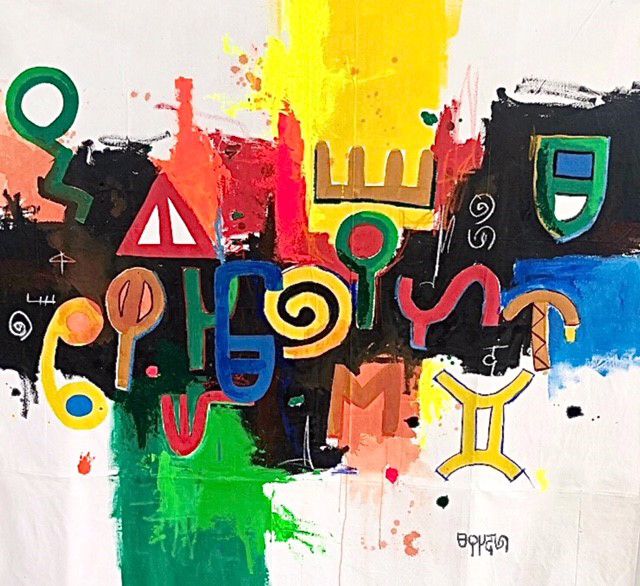

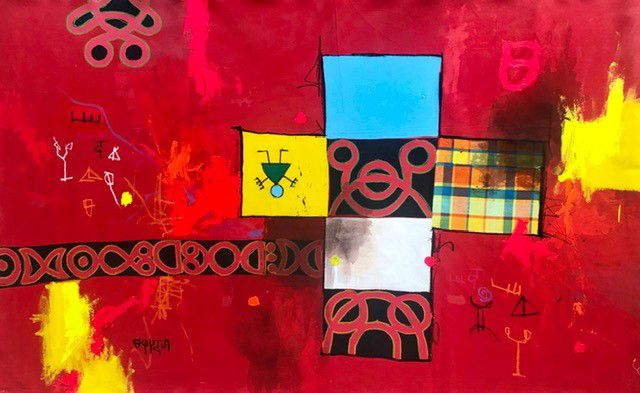

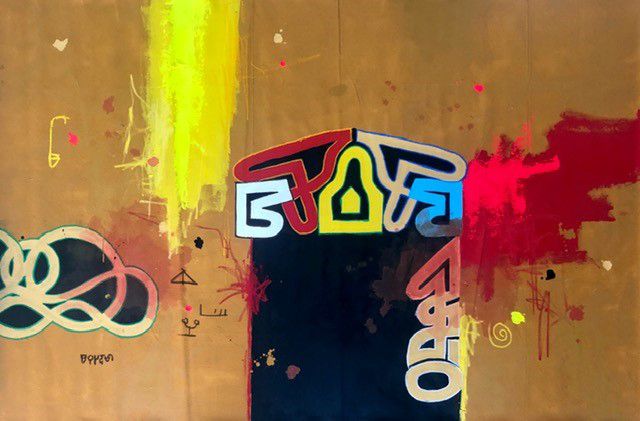

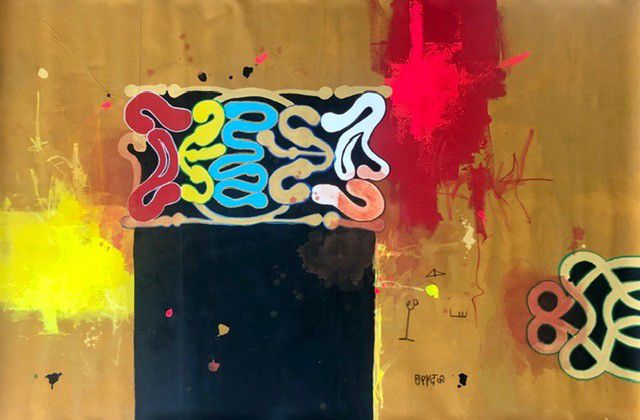

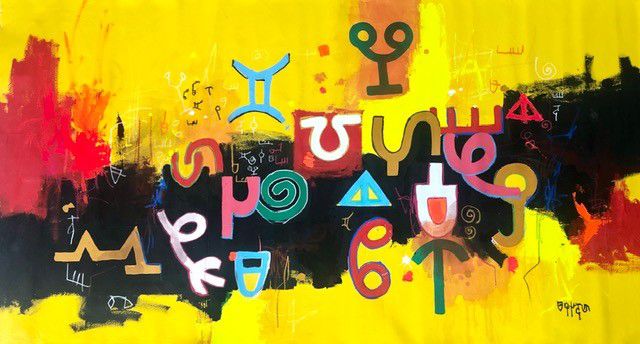

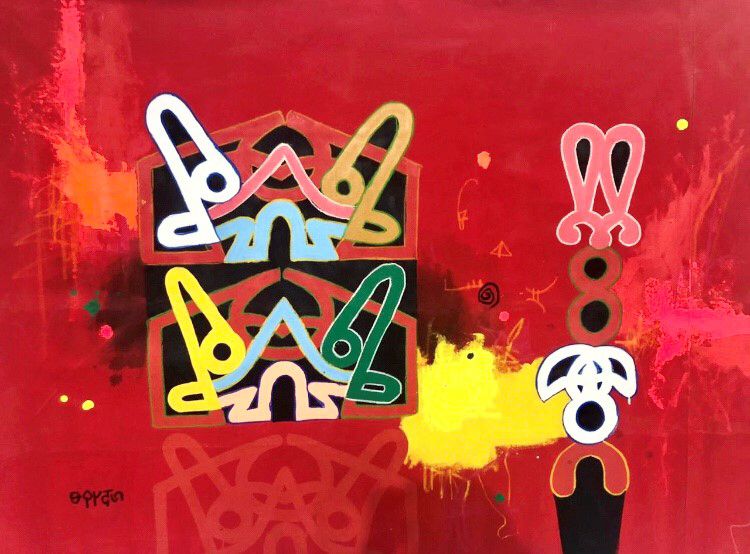

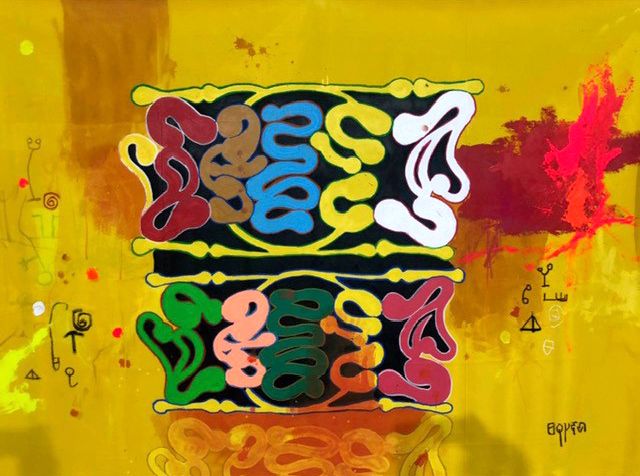

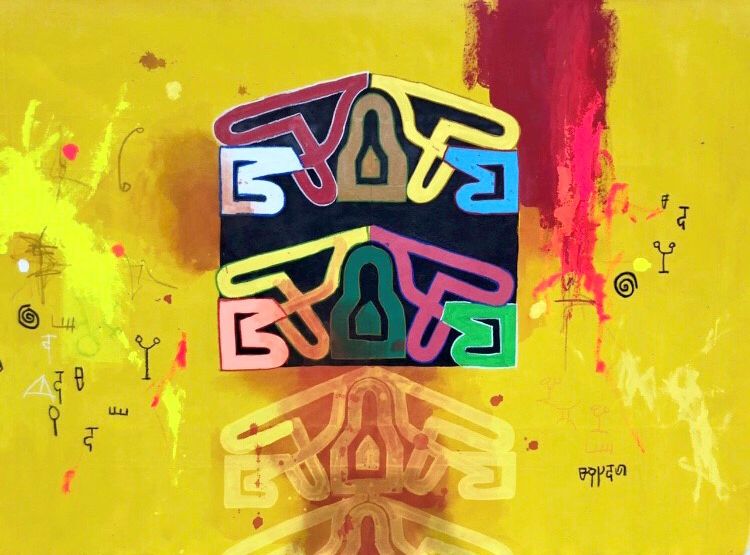

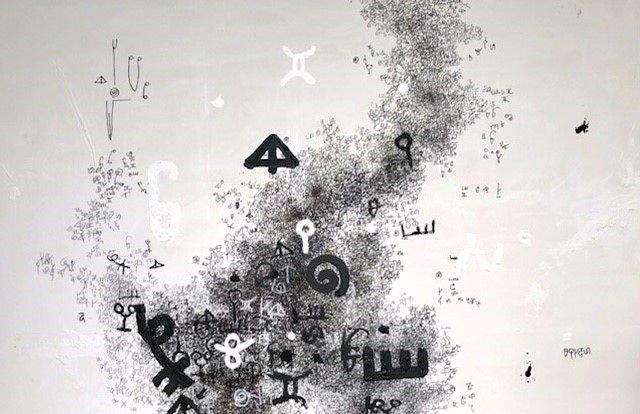

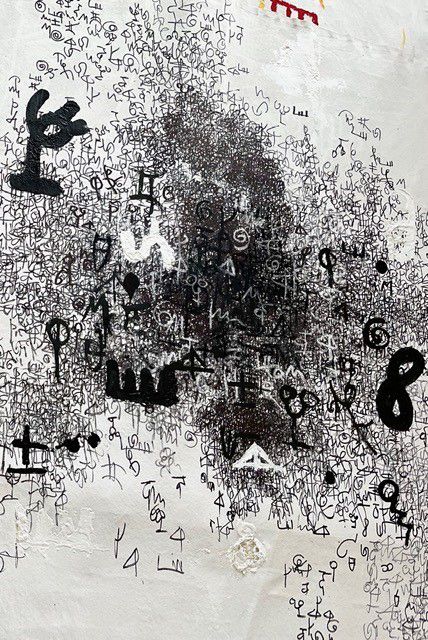

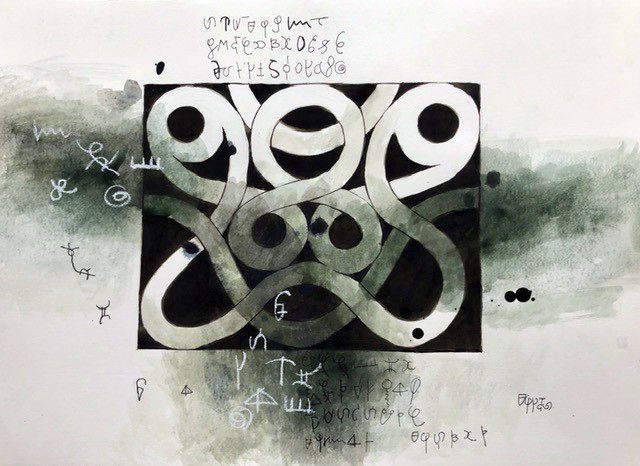

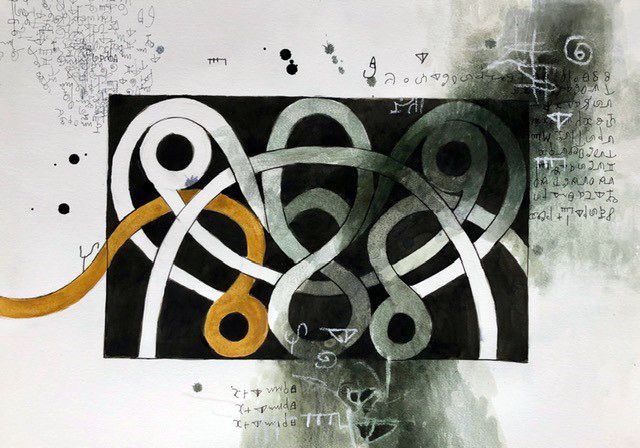

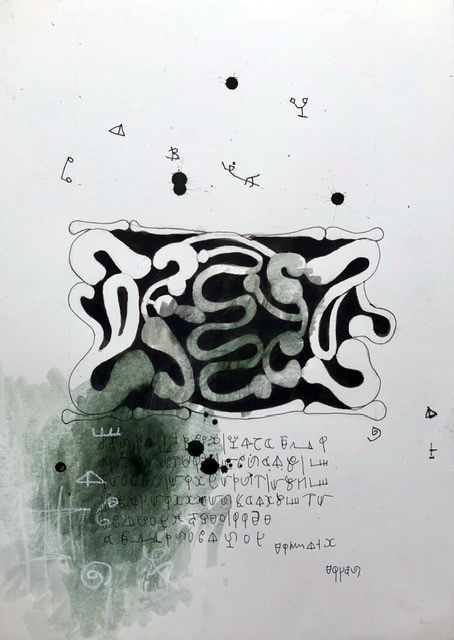

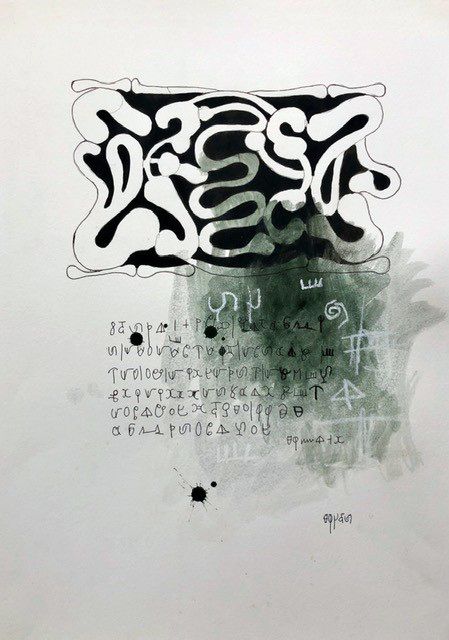

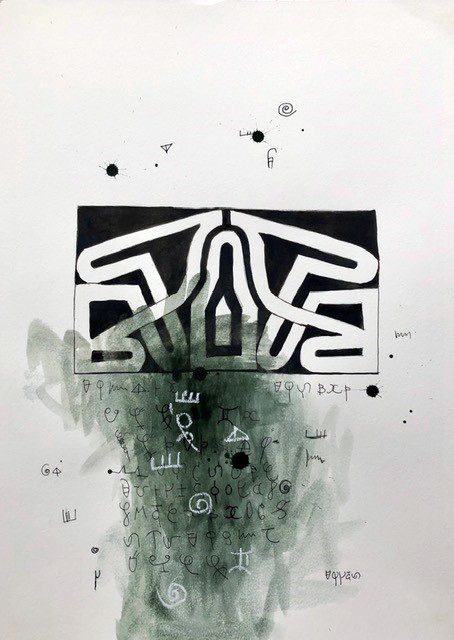

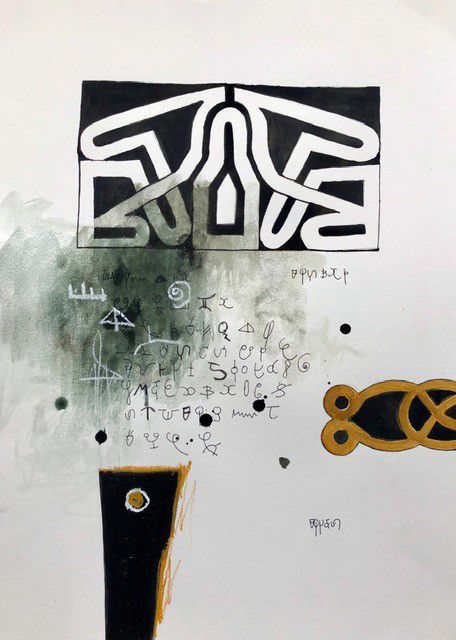

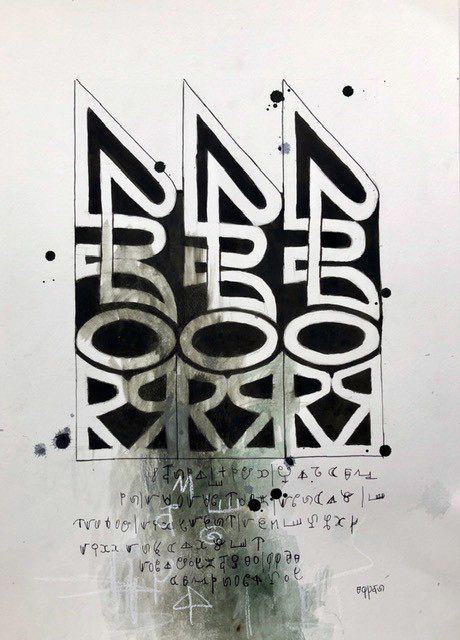

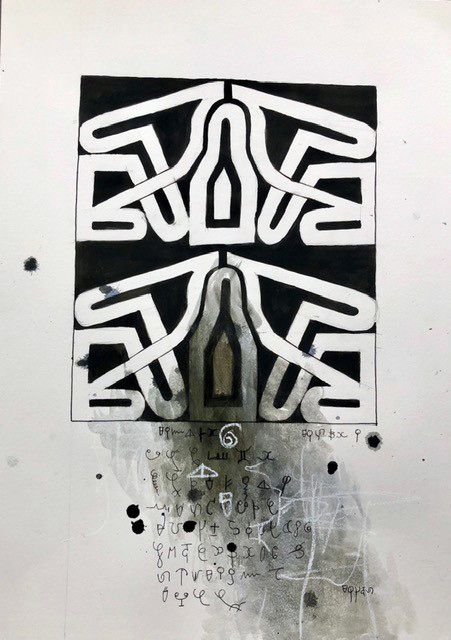

Post Jamaica, the paintings Pinas produces are a marked departure from his previous competent, attractive and light-hearted work. The depiction of reality is abandoned. He goes in search of his own visual language.

The first thing one notices is the bright colours. They refer to the colourful decorations that the Maroons arranged in and around their houses, which in turn reflect the colours of nature in its many, rich hues. Since the colours from one period are darker than from another, his pre-2000 pictures are particularly somber, the mood under which the canvases are produced probably also plays a part. His recent paintings have an almost exuberant quality.